According to Farms Under Threat: The State of the States, a new report by American Farmland Trust, millions of acres of America’s agricultural land were developed or converted to uses that threaten farming between 2001 and 2016. The report’s Agricultural Land Protection Scorecard is the first-ever state-by-state analysis of policies that respond to the development threats to farmland and ranchland, showing that every state can, and must, do more to protect their irreplaceable agricultural resources.

The State of the States report shows the extent, location, and quality of each state’s agricultural land and tracks how much of it has been converted in each state using the newest data and the most cutting-edge methods. The Agricultural Land Protection Scorecard analyzes six programs and policies that are key to securing a sufficient and suitable base of agricultural land in each state and highlights states’ efforts to retain agricultural land for future generations. It offers a breakthrough tool for accelerating state efforts to make sure farmland is available to produce food, support jobs and the economy, provide essential environmental services, and help mitigate and buffer the impacts of climate change.

In Washington, the report demonstrates some clear wins. In comparison to other states, the overall threat to Washington’s farmland is relatively low, and our policy response has been strong. This is thanks – at least in part – to WA’s strong land-use planning program, and to the hard work of land trusts and other conservation organizations over the last several decades. That said, our work is far from over.

Agriculture is essential to Washington’s communities, economies and way of life. Agricultural land represents 36% of the state’s total land area, and with over 35,000 active farms and ranches, agriculture contributes $9.6 billion in revenue to Washington’s economy each year[1]. But in the last two decades, the expansion of cities, suburbs and exurbs has threatened our land best suited for growing our food.

The report shows that, between 2001 and 2016, Washington lost 97,827 acres of farmland – an area nearly twice the size of Seattle. While this loss represents just a fraction of Washington’s total agricultural acreage – only .6% – it has threatened the state’s most productive farmland. Of the land lost to development between 2001 and 2016, 31% was considered “Nationally Significant” farmland, or land best suited for growing food.

The research also reveals an alarming new threat: a land use category that has never been mapped before, which AFT is calling Low-Density Residential Development, or LDR. LDR refers to the process of farmland being converted to large-lot residential development, for use by farmettes and ranchettes, not working farms.

LDR land use compromises opportunities for farming and ranching, making it difficult for farmers to get into, or travel between, their fields. New residents unused to living next to agricultural operations often complain about farm equipment on roads or odors related to farming. Retailers such as grain and equipment dealers, on which farmers rely, are often pushed out. Farmers can be tempted to sell out for financial reasons, or because farming just becomes too hard in the circumstances.

And lastly – but importantly – as older farmers near retirement they sell their properties, too often to non-farmers. This means that new and beginning farmers have a hard time finding land, threatening the very future of agriculture. More often than not, the land prices in these areas have been driven up by the encroaching development, making it impossible for new farmers to afford to buy a farm. In Washington, agricultural land that was in LDR areas in 2001 was 70 times more likely to be developed by 2016.

Farms Under Threat also digs deeply into states’ policy response to farmland loss. The states that did best recognized the threats to their farmland and addressed them with strong policies. Washington is one example, ranking highly in the top 12 states. Leaders like Washington, with its strong land use program, have been effective in slowing development’s march by utilizing at least four or five of the six policies AFT and its experts identified as the most effective.

Yet while Washington’s land-use planning program serves as a model nationwide, more can, and should, be done. AFT recommends that states can take the following five high-level actions to secure their agricultural land base:

- Action 1: Analyze and Map Agricultural Land Trends and Conditions

- Action 2: Strengthen and/or Adopt a Suite of Coordinated Policies to Protect Farmland

- Action 3: Support Farm Viability and Access to Land for a New Generation of Farmers and Ranchers

- Action 4: Plan for Agriculture, Not Just Around It

- Action 5: Save the Best, but Don’t Forget the Rest

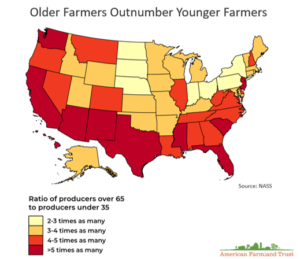

The growing demands on agriculture and the mounting pressures of climate change necessitate regionally diverse and resilient farm economies. At the same time, farmers are aging. In Washington, there are more than 5 times as many farmers over the age of 65 as under the age of 35[2]. As our farmers retire, at best, their land will go out of production. At worst, it may be sold and permanently lost to development.

The overall threat of farmland loss in Washington is deceptively low. While our agricultural lands are plentiful, our most productive, versatile and resilient soils are limited – and irreplaceable. Washington needs to act now to permanently secure its best lands. To achieve this goal, state and local governments must develop a comprehensive set of policies and programs that address not just land protection, but also farm viability and the transfer of land to the next generation.

AFT’s Pacific Northwest team will be hosting a webinar on June 19th for conservation stakeholders in Washington to dig into the report’s policy and spatial findings for Washington. Learn more and sign up here.

Addie Candib is AFT’s Pacific Northwest regional director and manages the organization’s programs in Washington, Oregon, and Idaho. She lives in Bellingham, WA.

[1] National Agricultural Statistics Service, 2017

[2] National Agricultural Statistics Service, 2017

Recent Comments